Oil Price Shocks and Forecasting Recessions

Last week...

- Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell’s speech at the Economic Club of New York reinforced his desire not to hike rates further at the November or December FOMC meetings. We believe the Fed will be on hold until economic data forces an additional series (i.e., more than one) of hikes.

- US bond yields continue to climb. The yield on the 10-year Treasury note hit 5% for the first time since 2007.

- In the face of higher bond yields across developed markets, global equities ended the week in the red.

- Economic growth in China has gained momentum following government stimulus efforts.

- Inflation in the UK Germany appears stuck at almost 7%, while Germany looks likely to fall into another recession this year.

This week, we’re addressing two commonly asked client questions: (1) understanding oil price shocks and (2) forecasting recessions.

Oil Prices and Forecast

As we mentioned last week, sharply higher oil prices are one of the risks of an expanded regional conflict in the Middle East. A historical example can be found in 1973 when members of OAPEC (Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries) instituted an oil embargo on countries that supported Israel during the Yom Kippur War. The price of oil increased almost 300% between October 1973 and March 1974, resulting in a US recession and double-digit inflation.

At the current time, oil prices are up about 7% since the terrorist attacks by Hamas on Israel and remain below levels we saw just last month, but an oil supply shock is a structural blow to the economy that’s worth considering.

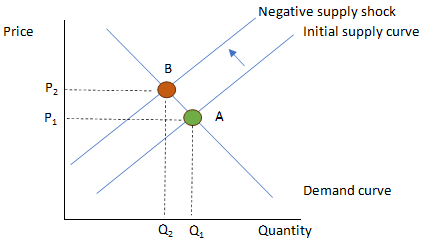

Back when I taught Econ 101, I would use an oil supply shock to get my students really thinking about the limits of monetary policy and the role of the Federal Reserve. I apologize ahead of time for using the same supply and demand chart in this commentary that my students had to suffer through.

An oil supply shock results in higher oil prices, which in turn means higher input prices for many goods and services in the economy. Producers have to raise prices to compensate and, in aggregate, the supply curve for the overall economy shifts to the left (Fig. 1). In isolation, the demand curve doesn’t change, but the intersection of supply and demand shifts up and to the left (from point A to point B) – resulting in an economy with higher prices and lower quantity sold. In macroeconomic terms, this means higher inflation and lower growth, or stagflation.

Central banks don’t have a good solution for supply shocks. They can raise policy rates to fight inflation, but that would further hurt growth. They can lower rates to support growth, which would inflame inflation. There’s no obvious policy measure that helps growth while also subduing inflation. In normal times, the Fed should just say “it’s transitory” (ha!), but that would be hard for them to communicate considering the post-COVID inflation hasn’t been completely solved.

Fig. 1: Impact of Oil Supply Shock on Supply and Demand in the Economy

Spotting Recessions

We’ll start by saying that any recession forecasting should be done with a huge grain of salt and a large dose of humility. Between 1999 and 2014, the IMF (International Monetary Fund) went 0-222 in predicting recessions among the countries it tracks. It was just last October that Bloomberg Economics, along with countless other forecasters, told us that a US recession was certain over the next 12 months.

What are we watching regarding early warning signals? Housing is important. As Ed Leamer, professor of economics and statistics at UCLA, published back in 2007, “Housing IS the Business Cycle.” Specifically, he said:

“Now that we know how important housing is to the US business cycle, the next step is to try to figure out why. One very big clue is that housing has a volume cycle, not a price cycle. Home prices are very sticky downward, and faced with a decline in demand, it is the volume of sales that adjusts not the prices. With the decline in sales volume comes a like decline in jobs in construction, finance and real estate brokerages.”

Currently, there are a near-record number of housing units under construction, so there is no indication of a recession yet, but that could change quickly next year.

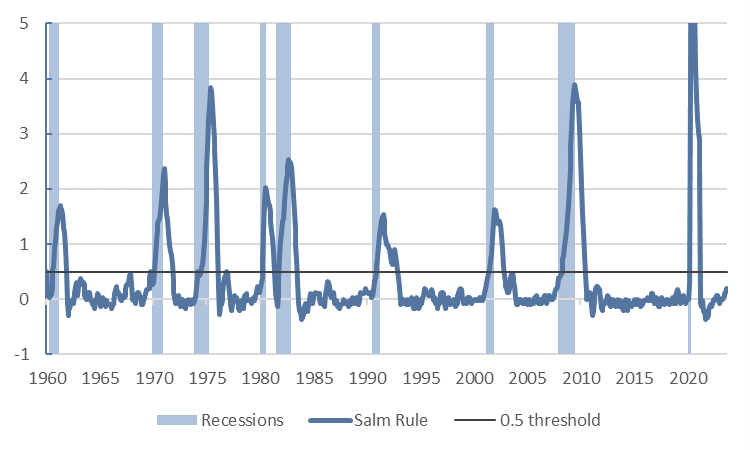

We also pay attention to the Sahm Rule as an indicator of the health of the US labor market. It is named after its creator, economist Claudia Sahm, and postulates that recessions are likely in the US when the three-month moving average of the national unemployment rate rises by 0.5% relative to its low point over the previous 12 months. There’s currently no indication from the Sahm Rule that a recession is imminent, although Dr. Sahm herself has said that she wouldn’t be surprised to see it fail as an indicator this time around.

Fig. 2: Sahm Rule, 1960- September 2023.

A final note – most recessions coincide with a market downturn, but all recessions are not equal. Germany, for example, appears likely to fall into a second recession within 12 months and has experienced zero growth over the last 1.5 years. Even so, the German labor market remains strong, and the German equity market has outperformed US equities over the last year. Recessions matter, but the type of recession matters even more.

We address two commonly asked client questions: (1) understanding oil price shocks and (2) forecasting recessions.

Download Document

Download NowDisclosures & Important Information

Any views expressed above represent the opinions of Mill Creek Capital Advisers ("MCCA") and are not intended as a forecast or guarantee of future results. This information is for educational purposes only. It is not intended to provide, and should not be relied upon for, particular investment advice. This publication has been prepared by MCCA. The publication is provided for information purposes only. The information contained in this publication has been obtained from sources that

MCCA believes to be reliable, but MCCA does not represent or warrant that it is accurate or complete. The views in this publication are those of MCCA and are subject to change, and MCCA has no obligation to update its opinions or the information in this publication. While MCCA has obtained information believed to be reliable, MCCA, nor any of their respective officers, partners, or employees accepts any liability whatsoever for any direct or consequential loss arising from any use of this publication or its contents.

© 2025 All rights reserved. Trademarks “Mill Creek,” “Mill Creek Capital” and “Mill Creek Capital Advisors” are the exclusive property of Mill Creek Capital Advisors, LLC, are registered in the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, and may not be used without written permission.