Investment Implications of Fiscal Dominance

Investment Implications of Fiscal Dominance

A participant in our Third Quarter Outlook Livestream asked a very good question, which we’ll paraphrase as “How will high fiscal deficits impact our ability to successfully invest over the long term and meet our legacy objectives for heirs and charities?”

Two recent papers have been helpful in forming our thinking about the long-term implications of our current fiscal outlook. The first is Olivier Jeanne’s (Johns Hopkins) “From Fiscal Deadlock to Financial Repression: Anatomy of a Fall.” The second is George Hall (Brandeis) and Thomas Sargent’s (NYU, 2011 Nobel Prize) “Fiscal Consequences of the US War on COVID.”

Hall and Sargent start with a basic premise – that “the public pays for what the government spends” – and observe that there are three ways to finance spending:

- Taking resources in exchange for a tax receipt (taxes),

- Borrow resources in exchange for an IOU (a bond), or

- Printing money and using the money to purchase assets from the public (currency).

From the public’s perspective, tax receipts are immediately worthless. Bonds and currency have value, but can become worth less (or worthless) if inflation is higher than expected. They frame this phenomenon as the government turning bonds and currency into tax receipts.

They then look at the War of 1812, the Civil War, World War I, and World War II as case studies for how the US government has handled previous periods of substantial unexpected spending. What they find is that the US has historically run something close to a balanced budget during peacetime and used a combination of higher taxes (#1 above) and debt (#2 above) to finance wars. WWI and WWII also required periods of high inflation (#3 above), which means bond and currency holders didn’t get back as much as they were promised in inflation-adjusted terms.

One big difference between our post-“COVID war” actions and those of previous wars is that we did not raise taxes or reduce spending after the war. COVID was financed primarily through IOUs (#2) and printing money (#3). A significant bout of unexpected inflation eroded the real value of bonds and currency, resulting in a transfer of wealth from the public to the government without requiring higher taxes. One way or another, the public pays for what the government spends.

Which brings us to Jeanne’s paper, where he asks a slightly different question: How do we avoid default when the current political situation won’t allow for higher taxes or lower spending?

As background, economists have developed theories on how monetary and fiscal policy work together. Monetary dominance refers to an environment where monetary policy (The Fed) focuses on inflation and fiscal policy (The Treasury) focuses on issuing debt in a way that doesn’t impact the economy. However, if the fiscal situation becomes untenable, we can end up in fiscal dominance where the central bank’s role becomes keeping interest rates at a level that makes fiscal policy sustainable. The years after WW2, when the Fed and Treasury worked together to keep interest rates low and accepted high inflation, are an example of fiscal dominance.

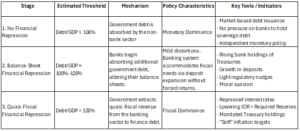

Jeanne finds that the path to fiscal dominance starts when countries exceed 100% to 120% of debt-to-GDP and can be summarized in three stages. For context, US debt-to-GDP stabilized around 100% after the financial crisis and 120% after COVID.

Source: Beckworth, David. (July 15, 2025) “Drifting Toward Fiscal Dominance.” Macroeconomic Policy Nexus. https://macroeconomicpolicynexus.substack.com/p/drifting-toward-fiscal-dominance

Based on Jeanne’s work, it’s not a coincidence that we have seen legislation introduced that will make it easier for banks to hold Treasuries and regulate stablecoins in a way that increases their demand for Treasuries along with plenty of political rhetoric oriented having the Fed adjust interest rates to better accommodate our debt burden. Stage 2 fiscal dominance, right on schedule.

Investment Implications

We’ll start by, once again, expressing hope that our representatives in DC find the political courage to either raise taxes, lower spending, or do both, but we’re not a policy think tank and hope isn’t an investment strategy. Frankly, we see little political enthusiasm for addressing our fiscal challenges. Tax receipts as a percent of GDP are already near all-time highs and spending cuts would have to come from entitlements, which politicians are loath to touch.

We believe the current path will likely result in a regime where fiscal pressures drive trend inflation higher, reducing the real return on US Treasuries and implicitly transferring value from bondholders to the US government. We’d also expect this outcome to pressure the dollar over the medium to long-term. The public pays for what the government spends.

Interest rate forecasts are more challenging. Higher trend inflation would usually result in upward pressure on interest rates, but if push comes to shove (e.g., stage 3 fiscal dominance), we could see the Fed and Treasury work together to set interest rates a la WWII.

A Crisis is a Terrible Thing to Waste

While this article has been depressing to write and perhaps somewhat alarming to read, we don’t want investors to overreact. The 10-year Treasury remains near 4.4%, which tells us we don’t have an immediate problem. Since we continue to expect Congress to delay action until a bond market crisis forces its hand, it could take years for any resolution. In fact, a mini-crisis in the bond market at some point in the future might be our best hope, as it could provide necessary political cover for bipartisan action.

A balanced perspective is important. Without fear of exaggeration or contradiction, we can say that the US remains the strongest and most dynamic large economy in the world. Our businesses are more profitable and our households have higher incomes and net worths than anywhere else, which provides a constructive backdrop for facing our fiscal challenges.

Back to the question at the heart of this article: “How do we successfully invest over the long term to meet our legacy objectives for heirs and charities?” We believe legacy portfolios should be well-diversified, equity-oriented, and hold assets that will do well across a range of potential economic regimes. Useful diversifiers can include farmland, real estate, private credit, private equity, and international equities, among other asset classes. Such a portfolio has historically performed well over the long-term and we expect it will continue to do so into the future.

Disclosures & Important Information

Any views expressed above represent the opinions of Mill Creek Capital Advisers ("MCCA") and are not intended as a forecast or guarantee of future results. This information is for educational purposes only. It is not intended to provide, and should not be relied upon for, particular investment advice. This publication has been prepared by MCCA. The publication is provided for information purposes only. The information contained in this publication has been obtained from sources that

MCCA believes to be reliable, but MCCA does not represent or warrant that it is accurate or complete. The views in this publication are those of MCCA and are subject to change, and MCCA has no obligation to update its opinions or the information in this publication. While MCCA has obtained information believed to be reliable, MCCA, nor any of their respective officers, partners, or employees accepts any liability whatsoever for any direct or consequential loss arising from any use of this publication or its contents.

© 2025 All rights reserved. Trademarks “Mill Creek,” “Mill Creek Capital” and “Mill Creek Capital Advisors” are the exclusive property of Mill Creek Capital Advisors, LLC, are registered in the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, and may not be used without written permission.