Tariffs, Then Dollars or Investments

Tariffs, Then Dollars or Investments

The big market-related stories of 2026 have been (1) international stocks outperforming US stocks, (2) interest rates moving higher, and (3) the gold price exceeding $5000 for the first time. What ties it all together? Downward pressure on the US dollar.

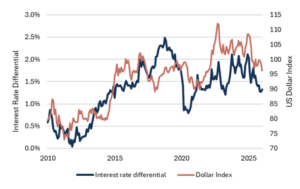

From a historical perspective, the US dollar remains strong, or expensive, depending on your specific perspective (Fig.1), but we believe the dollar will continue to face headwinds this year. Some of these headwinds will come from traditional economic factors like interest rate differentials, but we also expect renewed pressure on the dollar from the Trump Administration.

Fig. 1: US Dollar Indexes

Source: Bloomberg, Mill Creek. Data as of 1/28/26.

Our guide to understanding potential policy proposals remains Stephen Miran’s “A User’s Guide to Restructuring the Global Trading System.” Miran, former Chair of President Trump’s Council of Economic Advisers and now a Federal Reserve Governor, outlined what is better known as the Mar-a-Lago Accord (see “What is it good for?,” Feb. 10, 2025).

Many of Miran’s tariff-related proposals from the paper were implemented in 2025, so it shouldn’t be a surprise to see some of his currency proposals debated, if not enacted, this year. After all, there’s a section heading in his paper titled “Tariffs Then Dollars or Investments.” The blueprint is available for those willing to read it. We just added a comma in this article’s title to make it a bit clearer.

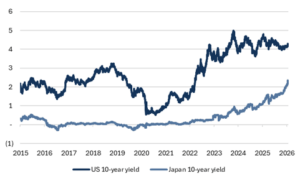

Interest rate differentials

We’ll start with interest rate differentials because they are currently the least controversial reason for dollar depreciation. US Treasury bond yields have been higher than bond yields for other developed countries since the global financial crisis (Fig. 2). These higher yields led foreign investors to buy dollars to purchase Treasuries (and other US assets), which pushed the value of the dollar relentlessly higher. The gap between US rates and the rates of other developed nations shrunk in 2025 and we believe will continue to do so this year. On the margin, a smaller interest rate differential will put downward pressure on the dollar as foreign currencies become more attractive on a relative basis.

Fig. 2: Interest rate differentials are closing

Source: Bloomberg, Mill Creek. Data as of 1/28/26.

Japan provides a great example. The interest rate on a 10-year Japanese government bond has jumped from 1.2% at the beginning of 2025 to 2.2% today (Fig. 3). Some prognosticators are worried about a Japanese bond market crisis, but we see a country with a growing economy, stimulative fiscal policy, a stock market that has gone up while their interest rates moved higher, and the same 2% inflation target that we have in the US. Investors should be asking why their 10-year bond yield remains 2% below US Treasury yields, not questioning why Japanese yields moved higher to start with.

Fig. 3: 10-year Treasury yields for US and Japan

Source: Bloomberg, Mill Creek. Data as of 1/28/26.

Mar a Lago, redux?

On to the more controversial headwinds for the dollar. The Mar a Lago Accord includes three dollar-related proposals that we believe are likely to come to the forefront in 2026: (1) direct currency intervention to weaken the dollar, (2) renewed pressure for the Fed and Treasury to work together in setting policy, and (3) taxation of foreign investments in the US.

Currency Intervention

It’s possible, but not confirmed at the time we are writing this article, that the Fed has already coordinated with Japan to strengthen the yen and weaken the dollar. Such a move isn’t insignificant from an investor’s perspective. Japan is currently 22% of the MSCI EAFE Index, which is a commonly used equity index for international developed market stocks, and dollar weakness against the yen will boost Japanese equity returns for US investors.

We could see additional bilateral currency intervention with other developed countries, but China remains the likely target of targeted currency intervention. We’re all familiar with President Trump’s perspective on the US trade imbalance with China, but it’s important to note that other developed countries are coming to the same conclusion. Just recently, French President Macron said “these imbalances are becoming unbearable,” European Union President Ursula von der Leyen said “For trade to remain mutual beneficial it must become more balanced,” German finance minister Lars Klingbeil said “We are not afraid of competition, but it’s also clear that it must be fair,” and Kristalina Georgieva, Managing Director of the IMF, said that China “continuing to depend on export-led growth risks furthering global trade tension.”

Now that there is a general consensus1 across political parties and developed markets that China’s $1.2 trillion goods trade surplus (Fig. 4) against the rest of the world is a problem, particularly since the manufacturing surplus is now believed to be above $2 trillion, we should expect increasing pressure on Beijing to allow Renminbi appreciation. The current situation is reminiscent of the early 2000s. At the time we had bipartisan support for tariffs on Chinese imports and the trade imbalance was eventually resolved through China allowing the Renminbi to strengthen against the dollar.

Fig. 4: China’s goods surplus against the rest of the world has exploded post-COVID (Billions)

Source: Bloomberg, Mill Creek. Data as of 1/28/26.

China is currently over 25% of the emerging market equity index. Even modest, controlled appreciation of the Renminbi against the dollar would be a solid tailwind for emerging market equity returns.

A Treasury-Fed Accord?

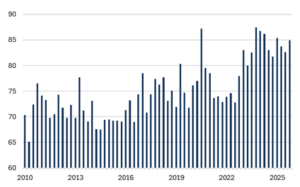

We continue to believe that the US is moving toward a fiscal dominance regime (see “Investment Implication of Fiscal Dominance,” August 4, 2025). Regardless of political jawboning about Fed policy, fiscal priorities (aka funding the federal deficit) are at risk of superseding the Fed’s monetary policy mandate of stable inflation and full employment. The Treasury now issues 80-85% of new Treasury debt as bills, defined as debt that matures within one year of issuance (Fig. 5). This means the Fed funds rate (the overnight interest rate) is an important determinant of forward-looking interest costs and therefore the Fed will feel the pressure, even if an official accord isn’t in place, to ensure those costs don’t result in a fiscal crisis. If Fed policy is biased toward a lower Fed funds rate, and the net result is higher-than-target inflation, the dollar will decline in response.

Fig. 5: Percentage of US Treasury issuance in bills

Source: Bloomberg, Mill Creek. Data as of 1/28/26.

There’s a secondary, but more-speculative, implication of a closer Treasury/Fed relationship. Miran points out (correctly2) that a third mandate of the Fed is “promote effectively the goals of… moderate long-term interest rates” which could include, in his words, “capping interest rates increases that occur as a side effect of Treasury’s intervention in foreign exchange markets.” In effect, if monetary policy or currency policy leads to rising long-term rates, the Fed can and should step in to keep rates at a reasonable level. This action wouldn’t be without precedence. The Fed intervened in Treasury markets to push long-term rates down after WW2 and after the global financial crisis. These potential actions, including a perceived loss of Fed independence, are likely dollar negative.

Taxation of foreign investment

We’ll keep this section brief as the proposals appear to be taking a backseat to tariffs and currency intervention.

If foreign investments in the US are taxed at higher rates, it makes US dollars and dollar-denominated investments relatively less attractive to non-US investors. The net result, all else equal, would be dollar depreciation. Miran proposes such a tax and the IRS published proposed regulation in mid-December 2025 that removes tax exemptions for certain foreign investments3. Our understanding is that the proposed regulations are quite narrow, but they’re part of the Mar a Lago Accord playbook nevertheless.

Implications for Investors

A weaker dollar environment requires a different investment playbook than what worked between 2010 and 2024, but our guidance for investors remains consistent:

- To the extent possible, achieve non-dollar exposure by diversifying equity portfolios outside of the US. Our international target allocation remains 34% of an equity portfolio, which is in-line with the global market cap of international stocks.

- Hold positions in assets that have limited or negative correlations with the US dollar. These assets include farmland, real estate, and infrastructure.

- Maintain an underweight in fixed income in favor or short duration, high quality private credit and other alternative income strategies.

More importantly, our 2026 outlook hasn’t changed. We expected dollar weakness in 2026. Economic growth remains strong inside the US and outside the US, corporate earnings continue to grow, and inflation has returned to a level that shouldn’t require meaningful changes to monetary policy. We’ve been adjusting portfolios for the current environment and policy outlook for some time and encourage investors to stay the course.

1 As evidence, here’s Paul Krugman agreeing, in concept if not in tactics, with President Trump about Chinese trade imbalances: https://paulkrugman.substack.com/p/chinas-trade-surplus-part-ii

2 https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/12/225a

3 https://www.whitecase.com/insight-alert/treasury-proposes-regulations-addressing-key-aspects-section-892-exemption-foreign

Disclosures & Important Information

Any views expressed above represent the opinions of Mill Creek Capital Advisers ("MCCA") and are not intended as a forecast or guarantee of future results. This information is for educational purposes only. It is not intended to provide, and should not be relied upon for, particular investment advice. This publication has been prepared by MCCA. The publication is provided for information purposes only. The information contained in this publication has been obtained from sources that

MCCA believes to be reliable, but MCCA does not represent or warrant that it is accurate or complete. The views in this publication are those of MCCA and are subject to change, and MCCA has no obligation to update its opinions or the information in this publication. While MCCA has obtained information believed to be reliable, MCCA, nor any of their respective officers, partners, or employees accepts any liability whatsoever for any direct or consequential loss arising from any use of this publication or its contents.

© 2025 All rights reserved. Trademarks “Mill Creek,” “Mill Creek Capital” and “Mill Creek Capital Advisors” are the exclusive property of Mill Creek Capital Advisors, LLC, are registered in the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, and may not be used without written permission.